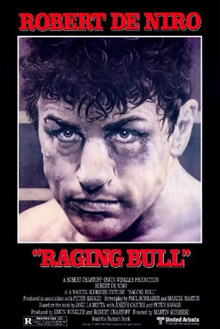

The decision that the Supreme Court may come to regret involved a copyright infringement lawsuit surrounding the script to the movie Raging Bull, which was released in 1980. In the film, Oscar-award winning actor Robert DeNiro played boxer Jake LaMotta.

An heir to the co-author of a 1963 screenplay about the life of the boxer apparently waited until 2009 to file a copyright lawsuit, claiming that the 1980 movie had copied portions of her father's screenplay without authorization.

The District Court in Los Angeles and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals applied the equitable doctrine of "estoppel by laches," borrowing the 3-year statute of limitations in the U.S. Copyright Act. Those Courts both found that the writer's heir had deliberately waited to file suit, prejudicing MGM which had released the film thirty-four years ago.

However, on Monday, in an unusual 6-3 split not along ideological lines, Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote for the majority, finding that the significant delay will not bar the heir from seeking damages or an injunction on a rolling basis, going forward.

The majority reasoned that each time a new Raging Bull DVD is printed and sold, there is a new independent act of copyright infringement potentially violating the heir's copyrights. Every new DVD that is printed, every time the film is broadcast on television or the film is re-mastered or re-released, is effectively a new act of infringement subject to the 3-year window going forward, not backward.

The end result is that copyright disputes that originated thirty or forty years ago -- or even in the more distant past -- can be resurrected and instituted now.

Justices Stephen Breyer, Anthony Kennedy and Chief Justice Roberts dissented, holding that the precedent would upset settled doctrine, and open up years of litigation over old wounds.

70-year old Jimmy Page, Robert Plant and others in Led Zeppelin presumably agree with the dissent's point of view.

In 1971, Zeppelin released the now iconic "Stairway to Heaven." According to some estimates, the song has earned at least $562 million since its release, a number poised to rise higher since Zeppelin is set to release new versions of its albums this summer.

Relying on Monday's Raging Bull decision from the U.S. Supreme Court, Time magazine reports that a new copyright infringement lawsuit has now been filed by representatives of the band Spirit, which released an instrumental song "Taurus" in 1968. According to the newly-filed lawsuit, Zeppelin opened for Spirit in the late 1960's, and was inspired to write the now famous guitar introduction to Stairway.

Relying on Monday's Raging Bull decision from the U.S. Supreme Court, Time magazine reports that a new copyright infringement lawsuit has now been filed by representatives of the band Spirit, which released an instrumental song "Taurus" in 1968. According to the newly-filed lawsuit, Zeppelin opened for Spirit in the late 1960's, and was inspired to write the now famous guitar introduction to Stairway.Direct evidence of copying may nonetheless be difficult to gather. Spirit's lead guitarist Randy California died in 1997 and documents showing copying, if any, were presumably lost to the mists of time.