A previous post discussed litigation related to the current status of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's copyright claims to the fictional characters of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, given that several works had passed into the public domain as a matter of US copyright law.

A previous post discussed litigation related to the current status of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's copyright claims to the fictional characters of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, given that several works had passed into the public domain as a matter of US copyright law.

Below is a further discussion

about the power of US copyright law to protect fictional characters that have

lapsed into the public domain, but which have been developed through

subsequent film adaptations and through the creation of "derivative works."

These legal issues are best illustrated by the murky copyright status of the iconic characters in the Wizard of

Oz.

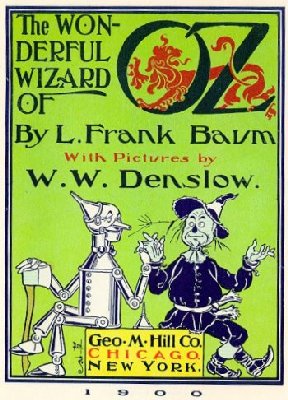

In May 1900, author L. Frank Baum published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a fantasy children's novel that included illustrations by W.W. Denslow. The book includes the familiar story describing how Dorothy, the Tin Man, Scarecrow and the Cowardly Lion traveled down the yellow brick road together to see the

Wizard so Dorothy could return home. Notably, in the original 1900 text, Dorothy's slippers are silver.

Baum's

seminal book was famously adapted to movie screens in the now iconic 1939

masterpiece film starring Judy Garland. This film made revolutionary use

of Technicolor, which inspired a change to the color of Dorothy's slippers to ruby red. Indeed, Dorothy's red slippers would later become enshrined in the Smithsonian Institution, as a testament to the importance that this particular prop played in American culture.

Although

the children's novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz lost its US copyright

protection in 1956, only the original novel by Baum and illustrations by

Denslow have entered the public domain.

Section 101 of the Copyright Act defines a "derivative

work" as "[a] work based upon one or more preexisting works" or

"[a] work consisting of editorial revisions, annotations, elaborations, or

other modifications, which, as a whole, represent an original work of

authorship." Therefore, the 1939 film in which Dorothy wore ruby red slippers is a derivative work that is still protected by US copyright, valuable rights currently held by Warner Brothers.

Slight differences between the public domain novel and the still-copyrighted movie are not an academic issue to those seeking to make any adaptation of the Wizard of Oz plotline without a license from Warner Brothers. And that includes Disney.

Indeed, just last week, Disney aired a brand new adaptation of the original Wizard of Oz called the Wizard of Dizz. In this version, Mickey Mouse and the Mickey Mouse Clubhouse troupe are recast as the characters from The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, with Minnie Mouse as Dorothy, and Professor Von Drake as the Wizard.

While the Disney adaptation is potentially protected free speech as a form of parody, a subtle but important detail is the fact that the ruby red slippers worn by Minnie Mouse are replaced by green shoes.

While the Disney adaptation is potentially protected free speech as a form of parody, a subtle but important detail is the fact that the ruby red slippers worn by Minnie Mouse are replaced by green shoes.

Was this detail an act of literary license on Disney's part, or part of a clever legal strategy to avoid a claim of copyright infringement?

In fact, Warner Brothers had litigated the status of the Wizard of Oz just two years ago, so it is more likely the latter.

In their most recent squabbles over this issue, Warner Brothers took the legal position that the characters from the film had so altered public perception, that virtually ANY unauthorized use of the characters would violate the film studio's copyright.

And (believe it or not) the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed, issuing a decision that left more questions than it answered.

Subsequently, additional unauthorized renditions including Oz the Great and Powerful starring James Franco, stirred up even more controversy, as Disney riled Warner Brothers by filing for trademarks on that name.

In conclusion, when fictional characters are first described in a text that falls into the public domain, the status of the original copyright does not necessarily make these characters free for the public to use without license.

Further, in Part III, we will discuss how trademarks and trade dress can theoretically create a perpetual "brand" surrounding a character that otherwise would be in the public domain as a matter of copyright law.